Glorious Technicolor

- Debra

- Mar 20, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 20, 2024

Spring 2019

Spring into Technicolor Resistance to Change What’s Old Is New! The forces that oppose change — and form resistance to change — rarely change. And their excuses are always the same. Decades ago, I offered to my supervisor, a Federal Section Chief Manager, the opportunity to grant me a work-at-home arrangement. I, the lowly civil servant, was chomping at the bit to change my life, but not to forego technical engineering writing for a living. My offer was flat-out refused. I asked why. “Well,” Mr. Bureaucrat gulped, “It’s never been done before.” “Now there’s a valid reason,” I quipped. Furthermore, I would be eating into the FTE’s. Full-time equivalent. The man-hours of each Federal employee are guarded like Fort Knox. And so I left the monotony of tried-and-tried-and-tired-and-tired to venture into the work of my own world In the Home. Never a dull moment there!

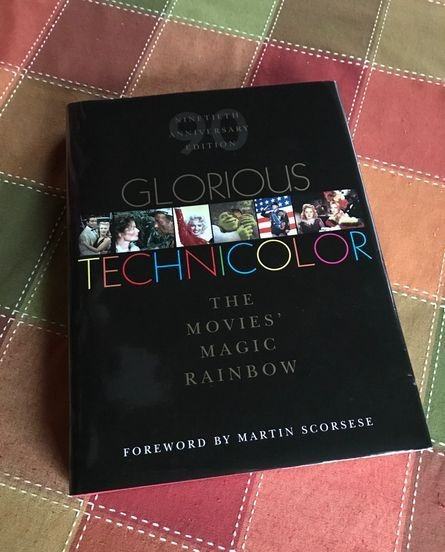

There is never a dull moment while I am currently engrossed in reading GLORIOUS TECHNICOLOR, The Movies’ Magic Rainbow, by Fred E. Basten. It’s a big book, with big ideas, telling the fascinating story of the history of color photography in motion pictures. I was inspired to buy this vintage book after watching, for the 4th time, the film documentary on the complicated history of the Technicolor Motion Picture Corporation. This documentary was produced in 1998 by Turner Classic Movies. It’s a Special Feature on my Blu-ray of The Adventures of Robin Hood, filmed in Technicolor and produced by Warner Brothers in 1938. Both the documentary and the book meticulously explore Technicolor, the brain-child of a man named Herbert Kalmus. They are highly recommended for entertainment and for enlightenment, as well as for an appreciation of how Professor Kalmus, the little MIT-Engine That Could, did create the earliest color process for filmmaking.

Mr. Kalmus believed in the adage “Never Give Up.” It is the most salient aspect of his success in convincing investors that his technical technique to create color film was worthy of investment — even when, technically, the process was still flawed and chronically spawned new problems as soon as the old ones were solved.

In 1925, during production of Wanderer of the Wasteland, Mr. Kalmus wrote of the constant fears among these innovative men who persisted in creating the process of developing, initially, a 2-color, and, eventually, a 3-color, film strip:

“ . . . A few of us in Technicolor carried the terrorizing thought that there was no positive assurance that we would finally obtain commercial negative, and that the entire Famous Players investment might be lost. . .”

The refusal from film-makers to take any risk — or to look to the future that became Hollywood — was a humongous stumbling block in the earliest days of Hollywood, circa 1925. One adherent to the concept of color in film was none other than a major player and one of the most luminous stars of the silent films of his era, Douglas Fairbanks. Fairbanks ardently, even passionately, wanted to film The Black Pirate in color. He expressed his thoughts in compelling prose to Kalmus. And while some of the mystery and mood of film have been sacrificed for vibrant color in movie-making, these arguments posed by Mr. Fairbanks aptly address the boilerplate cop-outs from the Song-and-Dance Resisters to Any Change at Any Time:

“. . . Not only has the process of color motion picture photography never been perfected, but there has been a grave doubt whether, even if properly developed, it would be applied without detracting more than it added to motion picture technique. The argument has been that it would tire and distract the eye, take attention away from acting and facial expression, blur and confuse the actions. In short, it has been felt that it would mitigate against the simplicity and directness which motion pictures derive from unobtrusive black-and-white. These conventional doubts have been entertained, I think, because no one has taken the trouble to dissipate them. A similar objection was raised, no doubt, when the innovation of scenery was introduced on the English stage — that it would distract attention from the actors. Personally, I could not imagine piracy without color . . .” And so piracy was filmed, in color.

Production of The Black Pirate, starring Douglas Fairbanks, cost one million dollars. This amount of money, in 1926, to make a motion picture was astronomical. The future of Hollywood, however, depended on that astonishing sum, and on the risk-takers. The swashbuckling of Errol Flynn in The Adventures of Robin Hood, in Technicolor, would be inspired by, and patterned after, the swashbuckling of Douglas Fairbanks in The Black Pirate and in his 1922 film Robin Hood. The risk-taker named Herbert Kalmus was very much a process-oriented man. He didn’t think primarily in terms of the finished product; he allowed his business partners to get bogged down with those finite details and demands. Kalmus was a visionary who dreamed in scenery of artistic colors and landscapes depicted by master painters.

Almost one hundred years later, the process is not the problem in film-making. It’s the content! I think it’s time for film-makers to go back to the story-drawing boards, the types of logical narration that Walt Disney and Alfred Hitchcock used. Going back to basics has never been done before in the weary, warped and repetitive world that has become known as Hollyweird. Maybe someone there can try change for a change!