Chapter 54 - The Roosevelt Chapter

- Debra

- Dec 6, 2025

- 6 min read

7 December 2025

It is always a rousingly inspirational experience for me to encounter Chapter 54 of THE DAWN. I call it The Roosevelt Chapter.

That sense of exhilaration helped me to rather quickly plow through my translation review of Volume II, Book 5, Pour La Victoire, of THE DAWN into L’AUBE.

During the several previous chapters of Book 5, How the Resistance-World Turns, Arthur Boucher Carmichael has returned to France from his U.S. Army mission-post in London. The timeline is January 1942. His parachutage into Provence does not go quite as-planned. He breaks his ankle and, through mysterious, infuriating, and miraculous circumstances, he gets to meet Camille again — after about a year of a separation that has done wonders to nearly freeze her heart toward this man.

The conditions under which they meet again might be part of the kismet that Arthur’s been seeking, but, initially, the glow of love-light feels much more like kick in the head, or the pants, to this Free French agent who hails from Colorado.

Chapter 54 returns Artur to being Arthur, the U.S. Army colonel who was in London at the time of Pearl Harbor. His thoughts, emotions, opinions, and initial steps toward forgiveness of the folly of humanity are presented before the narration journeys into the historic topics of the Great Depression in the U.S.A. — and the Dutchman from Hyde Park, New York who rose to the momentous occasion of saving America from all that might have doomed this nation in the 1930s and 1940s.

As a native Northeasterner, I’m quite familiar with the Roosevelt family, along with heated conversations about Franklin and Theodore, or Teddy. In my family of origin, these two Dutchmen were spoken of on a first-name basis, mostly because my father was a Dutchman, also of French Huguenot extraction, but of a much lower pedigree!

Whilst Moderns today complain about not being able to eat a Thanksgiving meal without the triggered vulgarity of the Family Leftist Wing-Nut at the table, I can attest to witnessing very substantial philosophical debates, not quite arguments, waged between my father and one of his older brothers regarding the Two Roosevelts (Roos-uh-velts) during not merely holidays, but any Tanis tribal gathering.

My dad was a conservative libertarian of the Goldwater stripe. He was a rugged individualist, who had worked as a bus driver, among many other jobs and financial schemes (owning a donut shop; being a bookie), before I was born. His “bad heart” (after two heart attacks) rendered him unemployed, and on Public Disability, which meant he believed he was “on the dole”. He therefore laboured as hard as he could with his creative, manual, and intellectual skills to cement a feeling of being productive.

He was thereby able to garner that vital sense of manhood that comes with feeling needed, and appreciated, as an able-bodied artisan. Work with his hands complemented work with his superior mind: carpentry projects; electronics stereo design and component assembly; building chicken coops for raising homing pigeons; gardening; construction of an outdoor bar-b-que, decades before the retro-chic fad of the dullard-parasites who presently feed upon the past for “new” ideas to rip off as their own.

His sibling was a self-made man who, after not having inherited the Family Farm (the older brother by 14 months got the farm) — started his own business: selling produce and canned goods on a rather inventive “fruit-peddler” truck that looked like awninged-shelving units on wheels.

You’d think that the self-made entrepreneur, the guy who invested his own hard-earned money in Blue-Chip Stocks for his retirement, would have been a hard-core capitalist, and not a socialist, enamoured of Swedish socialism.

Political philosophy, however, has much more to do with personality than intellect. As we have come to see, the thinking isn’t always there when it comes to viciously acting out a virulent sense of entitlement, selfishness, greed, resentment — all of those negative motivations that can drive a person toward an unkind fate.

I learned a lot about the willful forces that often drive a fractured human spirit toward an unkind fate — by the time I was ten years of age. The sagas of the Roosevelts are embedded in those lessons.

It was with a sense of foreboding that I embarked upon writing about the Two Roosevelts during the autumn of 2009. I’d theretofore been a fierce advocate of Teddy, Bully! and all that Rough Rider Stuff. I had mixed emotions, and opinions, about FDR. For the most part, I felt that he’d failed to trust the American people to do the choosing of A Future Leader. I firmly believed that he’d treated Charles de Gaulle horribly, with petty rancor, during World War II; and he had. Those stances remain unchanged in my book, personal and fictional.

What I didn’t expect to discover, to truly realize, as if for the first time, was the degree of reverence that I had for Franklin in writing of his dignified struggle to overcome physical, emotional, and mental turmoils. There was something within his bull-headed Dutchman self that transcended the self-indulged, privileged mortal he’d been, as I write in THE DAWN:

“His life took a perilous turn that next year, a momentous change which is said to have been unconnected to his sudden, rash decision to never run again for public office and instead pursue a lucrative profession as a New York lawyer. While vacationing in August 1921 at Campobello Island in New Brunswick, Franklin Roosevelt contracted an illness which was diagnosed by doctors as poliomyelitis. From that point on, this forceful, athletic man would never again regain the full use of his legs. He became a cripple, paralyzed, totally and permanently, from the waist down.”

It is not often that I re-read my writing and come away with a completely different appreciation of what I’d been composing, when I’d composed it.

I recall the week that I put together the first-and-only draft of this chapter. It was just before, and during, Thanksgiving of that dorky year, 2009. By November 2009, We the People had been obscenely lied to, on such a grotesquely amateurish basis, that I felt quite content indulging in the Great Crash of 1929, and the coffee-can mentality that saw adults stash their gold in coffee cans and bury them in them thar’ hills.

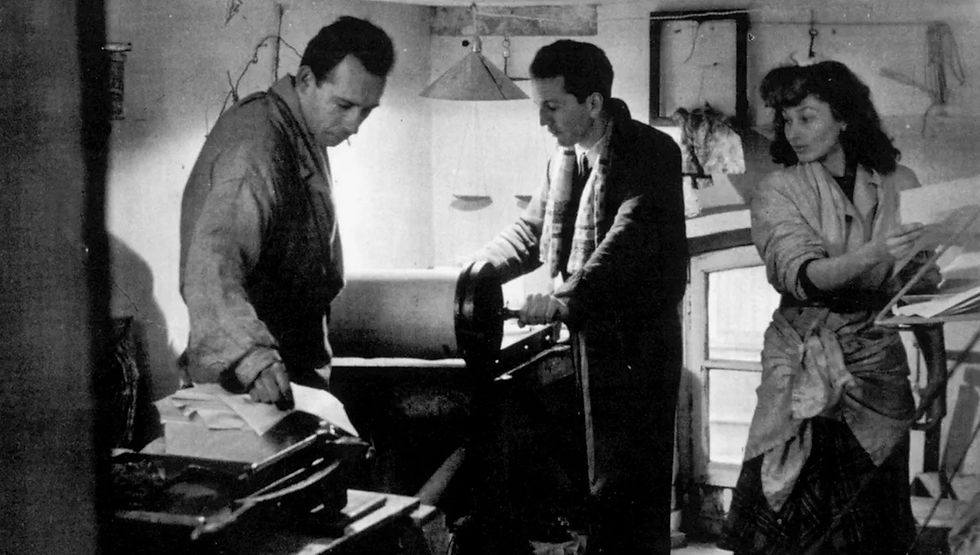

That Thanksgiving, in Placer County, was warm, as can be noted by my almost sleeveless top in that pic, taken whilst I composed The Roosevelt Chapter. I was happy then, very happy, and serenely confident. I was contently filled with a sense of moving forward in my life, personally and professionally.

My Very Dear Friend had just handed back to me her written comments on the physical pages of the chapters of Book 4, Operation Nottingham. That chapter, as I’d explained to her, “is The Military Part That Introduces a Love Interest for Camille.”

I can still recall how bored she was with this plot development!

As I look back upon those days, and nights, those blurrrs of time that were filled with busy busy schedules, chock-filled with duties, commitments, chores, work, meetings, frustrations, work, appointments, worries, more work, fears, fury over those fears, and endless questions to answers that had only begun to be identified:

I realize how The Forgotten Man and The Forgotten Women of those years, the post-Cold War years, are forgotten no-more.

I realize how many of my silently expressed emotions to my Very Dear Friend compel me now to make sure this translation is as good as she would expect it to be.

I realize how, my explanations and emotional opinions, expressed during the Fall Semester of 2008 to my dear College-Student Daughter, about this historic Address by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the Joint Session of the U.S. Congress on 8 December 1941 — were repeated, almost verbatim, in these paragraphs of Chapter 54:

Roosevelt usually did not write his speeches, although his address to the Joint Session of the U.S. Congress on 8 December 1941 was entirely self-written. That speech has never been surpassed in public addresses of that kind. Its barely controlled fury, directness of tone, profound logic, clarity of chronological narrative, compelling sense of inevitability, and its overall power still bring tears to the eyes of any listener.

And most Americans, as well as many foreigners, heard this speech, thus confirming the potency and magic of the auditory sense over the visual during times of intense grief and crisis. Once it was heard, that voice became an unforgettable tool of oratory. The masterpiece of measured sound became the hallmark of this unforgettable man.

Franklin Roosevelt would die before his tasks were completed as President of the United States. He would lead his nation from an introverted, fearful isolationism, feckless neutrality, and financial despair to glorious military victory and a productive economy, a colossus that would become the grandest machine of capitalism in the world.

America and the Allies ensured that the world would not be divided between free men, the franclings; and Nazi slaves. This unfortunate division would occur between free men and Communist lackeys, the workers behind the Iron Curtain in the so-called worker’s paradise of the Soviet Union and its satellite collectivized countries. America and her allies would fight that Cold War and also prove victorious over that evil.