Yvonne Ferrant: Tricks of the Trade

- Debra

- Dec 10, 2025

- 5 min read

Mid-December 2025

So much trust had been placed by Guillaume de Vallon in this one Frenchwoman — to be who she’d claimed to be.

Anyone can make an error in judgement. Guillaume de Vallon certainty did, more than once. Regarding Yvonne Ferrant, however, the mistake was yet another colossal betrayal of his trust.

When the fullness of this mistake was seen in the full light of day, Yvonne was in the dark with her latest paramour among self-destructive revolutionaries. This one was Philippe de Camay, the mangy Marxist.

Oh, what a tangled web we weave, when first we practice to deceive!

Yvonne could have typed those words on her calling card, but she likely would have made at least four typos!

As it was, when she came to call on Guillaume de Vallon, aristocrat-turned-resister during the summer of 1940, she was fresh from a series of unstable escapades with unsavory characters, herself included. Covering the tracks of her trollop past had become a full-time job for Yvonne; so, in one sense, she was very experienced in the subterfuge of faking her real self. The problem for this camp follower was that she couldn’t keep track of all of her lies, and her phony selves.

As things turned out, and they turned out tragically, Yvonne proved to be well past her prime as a femme fatale. She wasn’t feminine, merely fatal to anyone who came within her sphere of influence, and who expected to remain safe and alive.

That sphere of influence in wartime France expanded as the Dark Years inexorably moved from the Fall of France, through the Occupation, and toward Liberation.

Life in wartime France was filled with this type of half-baked floozie with a full-fledged death wish. Nowadays, she’d have at least 5 Instagram accounts, and too many TikTok videos, under too many fictitious names, which is so currently the norm, so Yvonne was well ahead of her time!

Chapter 57

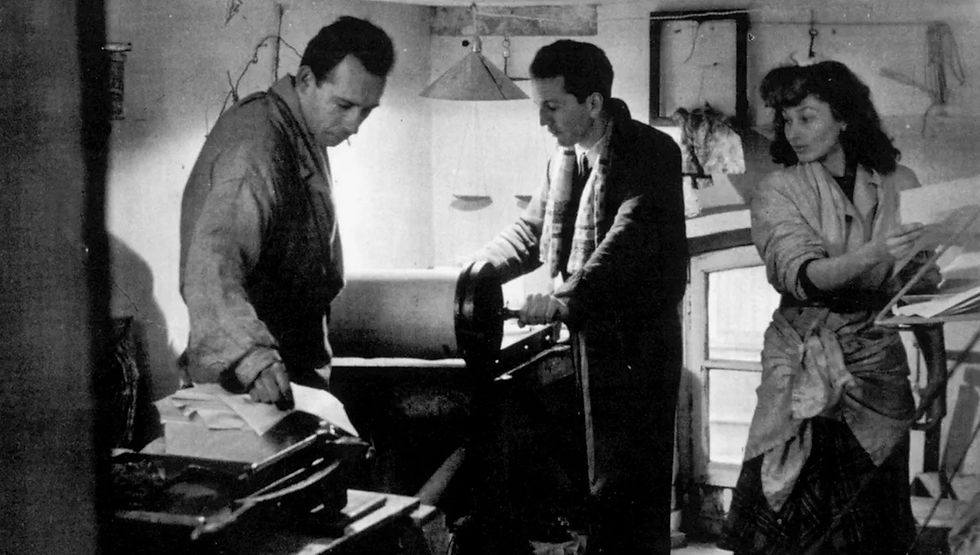

Artur was absolutely right. There were so many typographical errors in this covert newspaper of resistance that it nearly defeated its noble purpose. The stencil that had been cut for this mimeographed newspaper, Pour La Victoire, contained far too many typographical errors, or “les fautes de frappe,” for this journal to be taken seriously. Yvonne Ferrant had proven to be a very sloppy typist. Once la faute de frappe was inscribed onto the stencil, it was permanent. Guillaume had believed that the typing skills of Yvonne were quite good because this woman had boasted of her experience as a typist. She might have had massive experience, but she’d not learned from it.

Yvonne was a lousy typist. Guillaume was learning far too late that this flighty female had fabricated much of her past. It had become almost impossible for this Frenchman to extricate fact from fiction, truth from imagination, or fantasy from reality where Yvonne Ferrant was concerned.

The mimeograph that was used to create Pour La Victoire was an inexpensive printing press. It operated on the premise of forcing ink through a stencil that had been prepared by a typist. The enormous problem with this arrangement was that once the stencil was prepared, there was no way to correct it. Guillaume had been most enthused over the prospect of starting his own newspaper. He’d been proud of using one of several “machines à écrire,” or typewriters that he’d procured from the defunct Jardin Vallon. Guillaume had also purchased through le marché noir in Marseille a single-drum mimeograph machine.

Like so many other rebellious Frenchmen in wartime France, Guillaume de Vallon set out to become a one-man newspaper operation. The goal was not far-fetched. One enterprising person with a typewriter and the necessary equipment and supplies could essentially become his own printing press. Many savvy Frenchmen of resistance did achieve that goal. Guillaume yearned to be one of them, although he knew very little about how resisters in the north of France were publishing their clandestine newspapers. He proceeded with knowledge gleaned from his friend, Charles Beaumarchais, the editor of Le Figaro, and with the aching desire to disseminate the truth throughout Provence.

The ease of operation of this arrangement allowed abundant freedom from the need for many machine parts and trained personnel. Guillaume was thus armed with the anonymity and the concealment that were essential for a clandestine newspaper of resistance. There was no need for a typesetter since the composition of text was not performed through the physical setting of types, or metal parts. Simplicity of form demanded only the skills of one competent typist. Guillaume depended mightily upon her deft touch for the success of printing Pour La Victoire. Because he lacked his own typing skills, he did not know how to assess the abilities of any typist.

He’d trusted Yvonne to be honest in the appraisal of her own skills, and thus he’d moved quickly forward with the writing and preparation of his illegal broadsheet. Too late, he learned that proof was in the pudding, or rather in the print. Once the final product was prepared, it proved to be abhorrent. Proof-reading would not have helped because the stroke of the key upon the paper was the final deed; the one that remained permanent; the one that counted so very much and fell so far short of accuracy.

It wasn’t until the second issue was printed that Guillaume fully noticed the extent of the typographical errors. First he’d checked the typewriter itself. This act revealed his denial regarding the inadequacy of his typist. He’d then spoken to Yvonne about the typos. She said that she’d become a bit rusty in her typing skills, but she would improve with practice.

She’d only gotten worse, with or without practice. Guillaume had become infuriated with her, not merely for her shabby workmanship, but even more, for the basic lack of honesty that now underpinned her association with his newspaper enterprise. Yvonne Ferrant had become enamoured of the idea of having a thumb, or two, in the process of printing an illegal, clandestine journal of resistance. Guillaume had then discovered that this Frenchwoman was just plain enamoured of illicit activity regarding a newspaper.

His worst fears had come true when this statuesque, moody woman met Philippe de Camay during Guillaume’s absence from France in December 1941. During this time, Alphonse Bonner had taken charge of obtaining from Philippe de Camay the oil-based ink and card stock. This journal had grown in circulation to almost 2,000 within the Provence region; it needed more supplies as its readership increased.

Philippe had materialized one day with the materials at the garage of the Aubaine. Yvonne took just one look at that mangy male Communist, and she was smitten. She and Philippe soon became more than comrades-in-arms.