Chapter 35: Dominique

- Debra

- May 19, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: May 19, 2025

20 May 2025

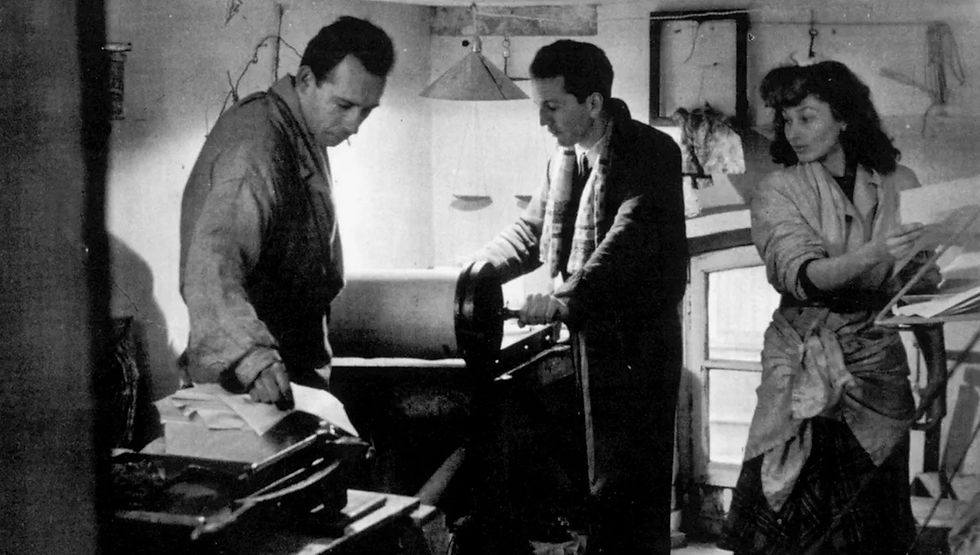

I am very grateful for having had the stabilizing force and grounded routine of home-making when I first created, or invented, the character of Dominique, sometime around 2010. I get scared for Artur, Colonel Arthur Boucher Carmichael, whenever Dominique enters the scene in Chapter 35 of THE DAWN.

Her entrance in L’AUBE is no less frightening!

I always feel a sense of duty to help my Colonel confront the cruddy facts of reality in Occupied Paris, January 1941. An American in Paris in January 1941 is not an MGM musical!

Artur had taken a single room in a moderately seedy hotel in Montmartre, the artist colony that was stuffed full of Communists and Socialists. It was the first trip to Paris for this American of French descent. He intensely disliked the fact that he had no prior basis of comparison for the City of Light that was now the City of Darkness. The stories which his French grandparents had told him about Paris belonged to a city so far back in time that it could not exist even in his imagination, not in view of the Occupation of this city. The netting and gray fabric covering the monuments and buildings obliterated any of his attempts to see Paris through the eyes of his Parisian forebears.

It was now Friday, 24 January 1941. Artur had been in Paris for five days. He was due to leave that next morning. The concierge of the hotel had left Artur alone, except to request daily that he dust the lampshade: “It will save electricity,” the Frenchman nodded as he confirmed this ridiculous modern fable of science.

Artur nodded and grunted, “Bien sûr.”

You might try taking off the lampshade, Artur dryly thought. One does not save energy, and, anyway, there was no electricity to “save.” There was also a paper shortage. The desk in the room contained no stationery, not even a pad of scratch paper. Logically, the pens had been removed from the desk drawer. There was a brown box radio, plugged into the socket in the wall, thereby inviting usage of electricity. With the volume turned down to a whisper and the door locked, Artur spent quite a few hours listening to various broadcasts at various times of the day and night. He discovered a great deal about the Germans and Vichy as a result of those wireless transmissions.

This brown box radio became for Artur an audio window to the conquered world of France. He listened intently to Radio Paris. The music was modern, the French singers talented and smoothly seductive. Overall, the programming was dexterous, insidious, sleek propaganda for the New Order, the New Europe, Hitler-Europe, and, ultimately, the German France. There was also a steady stream of anti-Semitic sarcasm and an even oilier flow of supercilious mockery of Vichy.

Artur was rather surprised to hear the cynical snobbish ploys of a male announcer who spoke in jest and in half-jest about the peasant; the provincial life; and the humdrum society devoted to family. Evidently, the Nazi model of life and Aryan reproduction did not revere the family unit as the building block of society. This credo completely followed the words of Mussolini, although it was possible that Benito had stolen this precept from Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda:

“Fascism accepts the individual only insofar as his interest coincides with the State’s.”

Artur smirked as he turned off the radio. If this society, or any society, did not base itself upon the unit of the family, then there would be no society. As much as this American disdained Philippe Petain, the message of this venerable man was accurate. Love of and devotion to family; love of and devotion to one’s country; national unity; sacrifice over indulgence: those virtues had stood the test of time. It was not, however, the job of Head of State Petain to lecture these virtues to the conquered people of France, in his insulting manner of further reminding them that the Fall of France was their fault.

Artur found it just a touch hypocritical that Philippe Petain was neither a father nor a family man, and yet he had cleverly positioned his face and his figure as the Father of France. This aging, adulterous, traitorous messenger looked slightly out-of-round from his message.

Artur hoped that the people of France would soon figure out that the Victor of Verdun was not only past his prime; he was past his past. His weary voice of sympathy too often switched over to the tone of harsh rebuke. There was too much insistence upon ideals that once upon a time had been gently woven into the fabric of French society. The old man was pitifully flailing as he tried to frantically mend ripped burlap rather than to spin silk into fine fabric. The State of France did not exactly represent the finest of French ideals, thought, or productivity.

And, now, Dominique arrives!

“Seul, monsieur?” Alone, sir?

Artur cocked his head up from his table-for-two. He took into full view a stunning redhead, a delectable woman who was a lanky, less pulpy version of Rita Hayworth. She wore a dress of sumptuous emerald green satin. The garment was simply designed, exquisitely tailored, and tightly fitted in a sophisticated yet seductive manner. This woman stood with her back halfway facing Artur. She peered over her shoulder at him. His eyes scanned the very low back of the dress that threatened to expose her derriere. Artur wanted to take his leather jacket and cover up her nakedness.

Daringly, she turned to him and smiled. Artur eyed the bateau neckline of this stunning dress. He then looked at her eyes which were light green, and at her skin, which was luminous and pale. He highly doubted that this female was a Frenchwoman. She looked too much like a girl from the Highlands of Scotland: lanky, lean, limber, long-necked, fair, and red-headed, with fury in her green eyes and far too much confidence in her movements.

“Je m’appelle Dominique.” The voice was shaky while it attempted to be sultry.

Artur bit his lip. This female either needed a drink or she’d had one too many. “Dominique” was, however, the name that he’d been given by an operative in London. She was to provide him with the names of any affluent resisters, especially organizers, in Provence. Artur had been asked by the Special Operations Executive to seek out any big fish who could assist the war effort in terms of organization.

Artur highly doubted that the real name of this seductress was Dominique, but he said in a low but genial voice his actual name, “Artur.”

Their eyes met. Artur was suddenly quite taken by the vulnerable look in her light green eyes. It was a hunger which said that she would gladly give her self to him for the night. He sighed softly. It did not seem likely that, having given her self to him for the night, she could be convinced to take her self back in the morning.

Artur had never known the easy unchastity of a demi-monde tart, but he had no desire to learn of it that night, or any other. It stunned him that the SOE would engage the assistance of a female who so willingly compromised her self and, with it, possibly her cover and vital information.

-----------------

Dominique does, in fact, provide Artur with a name that proves to be as compelling as it is mysterious: Guillaume de Vallon.

As for Dominique, she tried a bit too much to be compelling and mysterious in the midst of a Montmartre that contained more Nazis than French Communists. Her fate remains unknown, but Artur, and I, are very much on the same page of that unhappy ending.